RELIGIOUS AND CREATIVE STATES OF

ILLUMINATION: A PERSPECTIVE FROM

PSYCHIATRY

Philip Woollcott, Jr., M.D.

Prakash Desai,M.D.

Neither psychiatry nor religion has come to terms with the nature of mystic experiences. Use of the term mystical tends to imply either regressive psychopathology, an otherworldly state of religious bliss, or just plain mystification. Consequently, the study of mystic experiences has been pushed to the periphery of both psychiatry and religion. Scientific inquiry into the nature of reality has largely shunned these purely subjective experiences. In the religious sphere, Western orthodoxy has found incorporation of mystic experiences either unacceptable or at best a problematic enterprise. In Eastern cultures, such as India, both the clinical and the folk tradition regard mystic experiences as exceptional achievements, and mystics themselves as objects of veneration.

In this paper we attempt to bridge the chasm between religion and science in the study of mystic experience. We take as given the fact that some persons have such experiences, a reality that must be understood. We recognize at the outset that the major problem confronting discussion of the subject is the absence of a language in which to speak about these issues. As the mystic Suso stated, "Then did he hear things which no tongue can express" (Laski 1961, 367).

From the standpoint of science, the study of mystic states is related to a central problem of psychology-the enigma of consciousness itself and its various forms (John 1976). Our usual scientific methods of data gathering, analysis, and verifiability have not been to much avail in the area of those very aspects of consciousness that are most related to our humanity. We have as yet no scientific explanation for the qualities of subjective experience. Yet dreams and hypnosis have been investigated extensive. Mystic states await a formulation that will lend itself to further study. The pursuit of such a formulation is the purpose of our paper. Our approach will be phenomenological, with an orientation that attempts to integrate psychodynamic, physiological, and cultural features.

The subject of mystic experiences contains such a hodgepodge, such a variety of phenomena (James [1902]1958), that some sort of preliminary theoretical frame must be imposed on the data just to get started. Otherwise, the results depend upon which part of the elephant one has grasped. From the standpoint of scientific psychology, mystic and religious illumination represent a particular form of a larger spectrum of "discrete" states of consciousness (Tart 1977), each of which has its own specific characteristics. These states range from deep-sleep imagery to full-waking consciousness, including daydreaming, nocturnal dreams, reverie and other relaxation states, sensory-deprivation states, hypnagogic and hypnopompic states, inspirational creativity, psychedelic states, meditative states, States of rapture and religious ecstasy, states of dissociation, fugue states, and psychotic states, particularly hallucinatory states. Only the last three are clearly pathological (Fromm 1977).

Definition and Etymology

For the purpose of this paper, mystic states are viewed as sudden, time-limited altered states of consciousness (ASC) associated mainly with a subjective experience of the interrelatedness of all things. Mysticism is a pivotal element in religious experience, although not limited to religion. The word mysticism derives from the Greek, referring to those "who cover their eyes and lips" (Webster’s New International Dictionary, 1971). By closing off the senses, the mystic becomes disconnected from the anchoring effects of objects, thoughts, and perceptions. The mystic ASC is characterized by sudden onset, diffuse affect, a profound sense of unity or harmonious interconnectedness, and clarity of perception, especially the experience of light. When part of religious conversion or illumination, the cognitive content or "message" usually links the particular predicament of the individual to the broader social context, including, in the religious person, the Deity.

Psychology of Religious Experience

In a series of publications Philip Woollcott reported an analysis of the psychology of religious experience utilizing data from two sources (1962, 1969). The first comprised reports of patients, clergy, and other religious volunteers. The "research tool" used was an in-depth, relatively open-ended interview in which the subject was encouraged to describe any religious or mystic experiences beginning in childhood, emphasizing adolescence, and continuing to the present. The interview lasted ninety minutes to two hours and in approximately twenty cases was supplemented by a full battery of psychological tests administered by an experienced clinical psychologist (Pruyser 1968). The second source of data comprised published autobiographical accounts of religious figures, notably Augustine, Martin Luther, and Ignatius of Loyola (Woollcott 1966, 1963, 1969).

From these studies a number of psychological features stand out, which may be briefly summarized as follows:

1. Religious conversion must be understood not as an event but as a three-phased process: a preliminary phase, usually characterized by intense inner conflict approaching despair; the "illumination" proper, representing an altered state of consciousness associated with a subjective experience of interconnectedness which includes a vision or message; and a subsequent phase in which major shifts in values and meaning may occur, as well as character change and increased energy and resolve.

2. Moral and psychological conflict resolution is a prominent part of religious conversion. In the case of creative individuals, there may be a correspondence between the problem solving of the subject and existing social or religious problems (e.g., Martin Luther). As Bion has noted, the mystic may often become the creator for the social group that authenticates the mystic (1977), the mystic vision thus serving not only as a solution to the mystic's inner conflict but as a solution or new path for the existing culture or religious group to which the mystic belongs.

3. The role of self-restraint and limitation of sensual activity is a central feature of mystic experience. Disciplining of appetites and desires is the sine qua non of the mystic way and the first step in the achievement of samadhi in the traditional Yoga tradition (Eliadc 1975). This is equally true of the monastic mystics of the West, but such discipline has been largely forgotten in contemporary or "popular" meditation training in the West, which often begins with the postures.

4. The crux of significant religious experience is often the mystic component, and new religions are given birth in the experience of mystic enlightenment of their creator. The test of "authenticity" of mystic illumination is the enduring effect on the personality of an expression of a deep identification with all others and the world, as experienced in some form of "creative" action, usually in the social sphere.

5. Experiences of religious illumination are often associated with formation of adaptive "transitional phenomena" or "illusions" (holy objects, myth, rituals) that bridge the chasm between the mystic’s inner vision of unity and interconnectedness and existing religious and social beliefs. In other terms, the rituals and beliefs of the religious tradition arc revitalized and challenged by the mystic vision. Modifications in existing religious beliefs or rituals brought about by the mystic vision may in time become codified themselves, to be eventually again "disrupted" by a subsequent mystic vision. Thus, the development of religious belief seems to follow a developmental model of homeostasis followed by disruption, followed by a new, more evolved homeostasis. Such a model has been described as a basic organismic evolutionary process which can be identified in child development (Kegan 1985). A similar pattern has also been observed in the evolution of social systems and ideas (Kuhn 1962).

6. Normal and pathological narcissism are central to the religious Struggle, and aggrandizement is the main psychological hazard of religious illumination or conversion. This risk has been recognized and described by the monastic traditions (Merton 1967) and in the Hindu tradition (Saradananda 1978) in the East. Various pathological outcomes of mystic experiences arc described in a subsequent section.

7. The psychological essence of "mature" or "creative" religious illumination is not regression or need gratification but integration of dissociated elements into conscious experience. Divisiveness, scapegoating, and fanatic beliefs arc indications of a miscarriage of the mystic illumination. A "healthy" or creative result is an integration involving not only the inner life of the mystic but also a perception of a common ground in ideas, things, and persons previously considered disparate, if not contradictory. The true mystic, in short, sees harmonious interconnection not previously recognized by others.

8. The more creative mystics seem to have a relationship as an essential ingredient. This relationship has a "sublimating" effect, channeling the "mad" excesses of the mystic’s experience and behavior, e.g., Sri- Ramakrishna. Suicidal depression, hallucinations, and confusion arc frequently associated with the mystic "breakthrough" experience, even in cases of the great saints and religious figures.

9. The phenomenology of the mystic illumination for the religious Subject and for the creative writer, scientist, or artist is largely indistinguishable. Often religious language is the only one available to express the intense affects and psychological alterations of the illumination experience. The individual's language, culture, and values strongly influence mystic expressions, their content and interpretation.

Review of Literature

The classic description remains William James’s The Varieties of Religious Experience ([1902] 1958). James described a progressive obliteration of space, time, and the sense of self to the point of dissolution, a transient enlargement of the perceptual field, a sense of union with the universe, together with a sense of revelation by means of a direct perception associated with depths of truth and lucidity beyond ordinary experience. The world appears new and luminous. James emphasized that the language of music and poetry was better suited to communicate such ineffable experiences. James, who had such experiences, saw them as a return from the solitude of individuation to a merger with the all.

Freud's most explicit statements about mystic experience are mainly in two publications: the first chapter of Civilization and Its Discontents and one of the metapsychology papers, On Narcissism. Freud came to discuss the "oceanic feeling" as a result of his correspondence with Romain Rolland.

In commenting on such an experience, Freud made several observations. In the first place, he recognized the reality of such a Subjective state and allowed that in a particular situation, namely that of being in love, the loss of ego boundaries was normal and natural. "There is only one state-admittedly an unusual state, but not one that can be stigmatized as pathological.... At the height of being in love, the boundary between ego and object threatens to melt away. Against all the evidence of his senses, a man who is in love declares that 'I' and 'you' arc one and is prepared to behave as if it were a fact" (1930, 21:65).

Freud then went on to provide a theoretically consistent interpretation of such ego states. He stated, "our present ego feeling is, therefore, only a shrunken residue of a much more inclusive-indeed, an all embracing-feeling which corresponded to a more intimate bond between the ego and the world about it. If we may assume that there are many people in whose mental life this primary ego feeling has persisted to a greater or less degree, it would exist in them side by side with the narrower and more sharply demarcated ego feeling of maturity, like a kind of counterpoint to it. In that case the ideational contents appropriate to it would be precisely those of limitlessness and of an oneness with the universe-the same ideas with which my friend elucidated the 'oceanic feeling' " (1930, 21:68).

Freud was careful not to attribute pathology to the erasure of "every trace of sexual interests" in the anchorite or mystic meditator by emphasizing that "he [the anchorite] may have turned away his interest from human beings entirely and yet may have sublimated it to a heightened interest in the divine, in nature, or in the animal kingdom, without his libido having undergone introversion to his phantasies or retrogression to his ego" (1914, 14:80).

Federn (1952) conceived of an early split in the ego between the body ego, which follows the development of the self and object relations, and the "cosmic ego," which begins with the primary awareness of unity in the infant and remains in the unconscious throughout life. Despite theoretical difficulties related to primary narcissism and autoeroticism, Federn's view is closer to the thesis in this paper. Freud also viewed the oceanic feeling as remaining with the individual throughout life (1930).

Hartmann and Lowenstein (1960) described "automatization" of certain ego functions as a part of psychic structure-i.e., those parts of the personality that "have a slow rate of change" (Rapaport 1951). Gill and Brenman (1959), in their studies of hypnosis, coined the term deautomatization to account for the undoing of certain ego structures and functions. Deikman utilized this concept of deautomatization to explain phenomena associated with mysticism (1963, 1966). By having subjects meditate on a vase for thirty minutes daily over a period of several months, Deikman was able to reproduce a number of the phenomena described by mystics: a quality of intense realness, unusual sensations, a sense of unity, ineffability, and transsensate phenomena. He thought that the liberated energy experienced as light during they mystic experience may be the core sensory experience of mysticism.

The emergence of modern psychoanalytic ego psychology, especially Kris's concept of regression in the service of the ego (1952), has led to a series of writings in which mystic states, as well as states of' creative illumination, are examined in a less reductionistic way.

Bach (1977) defines state of consciousness as an organized notion that emphasizes the primacy of subjective experience, ranging from more or less non-conscious to highly conscious, with a particular emphasis On the vicissitudes of self-awareness. There is in states of consciousness a dimension of subjective awareness that has its roots in diurnal variation.

From a quite different perspective, E. R. John, in a recent review, defined mind (under which rubric he subsumed such phenomena as consciousness, subjective experience, the self-concept, and self-awareness) as an "emergent property of sufficiently complex and appropriately organized matter." However, John pointed out that reality is not our experience of reality. What dimension or aspect of this cooperative interaction of processes "might produce the rich, diverse qualities of this abstraction from reality (consciousness)" is unknown (1976, 45).

As these two latter viewpoints indicate, consciousness itself is not readily defined, and the particular definition depends on the orientation of the definer. At least four different orientations are relevant to this discussion: (1) physiology, (2) psychology, (3) physics, and (4) philosophy. A detailed discussion of the varied components of consciousness as well as misconceptions concerning it is beyond the purpose of this study. 1,2

Tart (1977) has elaborated further on a typology of "discrete states of consciousness," defined on the basis of biological and physiological givens oil the one hand and by learning and acculturation on the other. He described a multidimensional space to map various discrete states of consciousness. Each dimension represented one of these components as a "hardware" or "software" variable in the "map."

Developmental Approaches

Margaret Little has proposed that a "primary unity" between infant and mother forms the basis of all subsequent relationships and very likely of the deeply moving experiences of nature, art, and religion as well (1981). Burrow (1964) termed this initial bond "primary identification" and attributed to it much the same significance as Little. What we know about this period of life is inferred from the observations of infants and, to a certain extent, from work with adult patients. This initial structure of the infantile mental life may be termed the "pristine ego" which we define as a primordial, largely neurobiologically determined structure of the mind, which exists from birth as a primary awareness, a state of consciousness in which there are as yet no distinctions. Our "essence," to the extent that we can become aware of it, is not yet an "I" but a unity of "I" and "other."

The study of human development has been conceived by Piaget less as a steady, unremitting process than as a series of homeostatic balances (Kegan's "evolutionary truce," 1985) interspersed with transitional disruptions, leading to a new homeostatic balance at a higher level of development. This cyclicity continues throughout life. In early life most of the changes arc characterized by physical predominance, in later life, by mental predominance. Each stage of homeostatic balance is characterized by a world and the meaning and value we give things (Piaget 1932). Generally, development moves from embeddedness to individuation, from fusion with the world to relationships, from egocentricity to sociality in an increasingly broad sense.

There is in Kegan's work a tension between self-preservation and self-transformation throughout development. It is our thesis that mystic states represent the evolving manifestations of an innate psychobiological (neurophysiological) propensity for unity, for affiliation with our fellowman and with the natural world. True mystic states represent a relatively rare form of unitary consciousness associated with a breakthrough or disruption of homeostatic balance. In addition to mystic states of unity, experiences of awe, rapture, the numinous, creative insight, and the so-called "eureka experience" refer to related states of unitary consciousness that tend to be dissociated from our ordinary "objective" consciousness.

Neurophysiological Approaches

Recent Studies (Galin 1978; Tuckcr 1984) indicate that people have the capability for at least two major modes of consciousness: a logical, sequential, analytic mode, which is processed primarily, but not exclusively, in the left hemisphere of the brain; and an intuitive, holistic mode that develops primarily in the right hemisphere. It would appear that mystic disciplines attempt to enhance "intuitive" knowing associated with the right hemisphere integrated with enhanced clarity and "one pointedness," which may represent left-brain activity. Mystic disciplines and meditation thus may promote integration and rebalancing of left and right hemispheric functions (Deikman 1966). The sudden appearance of mystic states suggests a phenomenon in the brain similar to what has been described as "kindling" (Racine, Burnam et al. 1973).

According to Goleman (1976), meditation delinks the limbic neurophysiological arousal patterns through attitudinal modification (similar to biofeedback). However, he contends that meditators are characterized not only by limbic inhibition but by greater specific cortical alertness. The experience of the self and the state of consciousness vary with each "deepening" level of meditation, with advanced meditators reporting obliteration of all perception and, finally, a state where there is neither perception nor sense of self The latter is experienced as a unity with the all or cosmos.

D'Aquili (1986) has described an "aesthetic-religious continuum 5 " one pole of which is represented by the aesthetic sense and the opposite pole by what he terms the epistemic mystic state of absolute unitary being (AUB).

When in the state of AUB, which would appear to correspond to the true mystic state, people lose all sense of discrete being; the difference between self and other is obliterated; there is no sense of passing time. Such experiences are often described by religious individuals as a perfect union with God-the unio mystica of the Christian tradition. This is a rare state, according to d'Aquili, and possesses a sense of transcendent wholeness without temporal or spatial division.

According to d'Aquili, these rare AUB states are attained through the "absolute" functioning of the "holistic operator," the neurological substrate which is probably the function of the parietal lobe on the non-dominant hemisphere. However, d'Aquili makes the interesting proposal that during AUB there is not only maximum discharge from the holistic operator and other neural structures on the non-dominant side, generating a sense of absolute wholeness, but also a Simultaneous maximal firing of structures On the left or dominant hemisphere. Therefore, the experience of absolute unitary being is not a sense of merger or undifferentiated wholeness only, but also, and paradoxically, a state of intensive clarity of consciousness and perception, since both hemispheric systems are maximally firing.

D'Aquili proposes that whenever the sense of wholeness exceeds the sense of discrete elements, there is an affective discharge via the right brain-limbic connections. This tilting of the balance toward an increased perception of wholeness, depending on its intensity, can be experienced as beauty, numinosity (religious awe), religious exaltation, or finally, AUB.

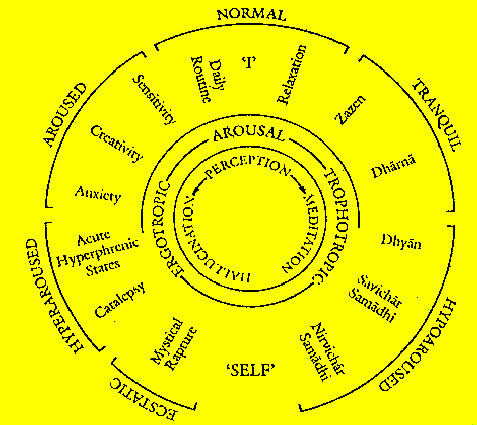

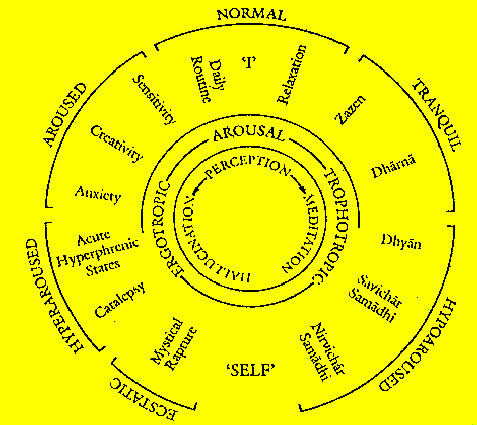

Fischer, in his study of yogic samadhi (attainment of inner light), presents a cartography of various states of consciousness. (See Figure 10.1.) Fischer’s conception, that ecstatic mystical rapture and yogic samadhi may arrive at a similar endpoint through quite different paths--tropotrophic or ergotropic-- is a useful one. Fischer's diagram (1975) represents one of the few attempts to integrate psychological, physiological, and "religious" categories.

Figure 10.1

Varieties of Conscious States

Caption for Figure 10.1

Varieties of conscious states are mapped on a perception-hallucination continuum of increasing ergotropic or hyperarousal (left half) and a perception-meditation continuum of increasing tropotrophic or hypoarousal (right half).

Note that a labeling in terms of psychopathology has been emitted from this map. Hence it is perfectly normal to be hyperphrenic and ultimately ecstatic in response to increasing levels of ergotropic hyperarousal. The creative rapture of a St. Teresa, however, will envelop the cognitive repertoire of the whole perception-hallucination continuum. The radiating center of this repertoire may he the ecstatic state characterized by a very high sensory-to-motor ratio, and an erotic euphoria or orgasmic intensity Visualize Bernini's rendition of St. Teresa's ecstasy (Peterson 1970). An analogous very-high-sensory-to-motor ratio is also characteristic for the most hypoaroused state: nirvichar samadhi; recall the picture of Ramakrishna in samadhi (Lemaitre 1963); his smile very closely resembles a euphoric-orgasmic mystical smile. A subsequent publication should separately cartograph states of consciousness during sleep, certain composite (drug-induced) states and those states of consciousness that can be assigned to the realm of psychopathology. SOURCE: Fischer 1975: 234.

Julian Davidson (1976) emphasized shifts between physiological states of trophotropic and ergotropic stimulation as inducing altered states of consciousness, including mystic states of unity (samadhi). However, he felt that the specific determining factors belong with set and setting (as with LSD research) rather than physiological phenomena.

Phenomenology

Suddenly, with

a roar like that of waterfall,

I felt a stream of liquid light entering my mind, I

felt the point of consciousness that was myself

growing wider surrounded by waves of light.

(Gopi Krishna 1974, 2)

Mystic states come suddenly, are generally dissociated, and cannot be predicted, although certain disciplines may increase the probability of their occurrence. Mystic states are temporary phenomena, rarely lasting for longer than a few hours. Then they fade away, leaving vestiges of emotion, perception, and thought that in some cases may be experienced as having extraordinary and enduring meaning. There may be associated creative insights, enhanced energy and resolve, and a sense of inner peace.

One may feel inspired to express the vision accompanying the mystic experience in some form, but the vision itself is ineffable. The very nature of mystic experiences tends to exclude them from the "real" world, its strivings and practical demands.

The phenomenon of mysticism is more than a feeling. It has a cognitive component that has persisted through the ages. If one examines the accounts of mystics, one perceives a common thread that runs through culturally and historically diverse documents: a deep identification with an beings, so deep and immutable that once envisioned, its repudiation seems to divide the self against itself In some cases, an experience in youth is "reviewed" and reassimilated at subsequent stages of life, even into old age (Syz 1981). In the mystic illumination the subject feels convinced of this unity with others and the world.

Because of the power and at times blissful nature of mystic states, people have attempted throughout history to cultivate them. The methodology of this cultivation varies but inevitably involves creating an ASC, often through a combination of regulation of breath and control of thought, or deprivation or regulation of the senses.

Mystic states, including religious and creative illumination, are related psychologically to other "breakthrough" experiences such as trances, faith healing, hypnotic phenomena, and, on a pathological level, to multiple personality. In all of these there is a sudden breakthrough of previously dissociated or unconscious aspects of experience into consciousness, resulting in a broader, more integrated and in some cases a novel or new field of perception and thought.

The after-effects of mystic and creative illumination often include a sense of rejuvenation and newfound energy, liberation from prior conflict and depression, a profound sense of joy, and a sense of having "another life," or a "new world" (Laski 1961). In religious subjects, a feeling of closer contact with the Deity, with other people, and with the nonhuman universe as well is frequently described (Searles 1960). In this respect, this state is not unlike the feelings described by those in love.

A sense of new knowledge in the form of a message or vision is often described-a message that resolves or transcends previous painful contradictions or personal struggles by linking the conflicts of the subject with broader social values:

The necessity to find ever-new solutions for the contradictions in his existence, to find even higher forms of unity with nature, his fellowmen, and himself, is the source of all psychic forces which motivate man, of all his passions, affects and anxieties. (Fromm 1955, 25)

A sense of greater coherence and expansion of the self is common. At times this results in a grandiose or megalomanic identification with the Deity. This indeed was the outcome of one of Saint Ignatius's earlier "partial" conversions, prior to his famous experience at Cardoner. Ignatius reported, following this prior ecstatic experience an elated sense of "vainglory" which did not last and which was followed by a depression. Following his enlightenment at Cardoner, his vision sustained him through long hardship. This second illumination, although more creative and productive, was accompanied by a pronounced humility (Woollcott 1969).

The aftereffects of the "higher" forms of mystic illumination tend to be creative, adaptive, socially valuable-not grandiose, divisive, or schismatic. However, the effects of religious illumination may be radical and controversial vis-a-vis existing social values. What is especially noteworthy in the aftereffects of the higher mystic illumination is the attitude of dedication and commitment, rather than strident or polemic efforts.

A feeling of renewed physical health and vigor without anxious or hypomanic drivenness is commonly described. This "healing" effect of mystic illumination is in need of much further study. The psychoanalyst Nathaniel Ross has stressed the importance of "an objective and dispassionate study of whether religious or mystic claims to have improved or enriched human relationships is valid" (Ross 1975).

Creative writers have stressed the importance of the dissociated component of creative illumination. The more disconnected, the more forceful the "vision the more it is "surrendered" to, the more likely it is to be Cctnic poetry" (George Eliot, in Laski 1961, 306). This ability to "turn off" the thoughts and reactions that usually filter and organize what is perceived, to be open, and to "surrender" illumination is found in both religious and creative people who seem to have had intense and life changing experiences of illumination.

Archaic types of mystic illumination may be distinguished from more "creative" developmentally evolved forms of mystic consciousness along three axes: (1) degree of clarity of perception, (2) degree of integration versus projection, and (3) level of moral or ethical development as reflected in relationships. Generally, regressed merger states are characterized by a lack of clarity and relatively primitive moral and psychological development. For example, fanaticism may be associated with pseudoreligious ecstasy, a high level of perceptual clarity, but with marked projection, often of paranoid proportions, and highly disturbed ethical development-self-righteousness, omnipotent grandiosity associated with amoral or immoral destructive hatred of the "scapegoat" (i.e., merger or unity at expense of projection). More creative mystic or unity states are associated with a paradoxical combination of intense clarity of perception (enhanced ability to make distinctions), profound sense of integration or interconnectedness (absence of projection), and highly developed moral behavior often associated with principles reflecting broader social concerns and repudiation of narrow, culture-bound prejudices. (See tables 10.1 and 10.2)

Table 10.1

A Developmental Psychology of Mystic States

| Dionysian Frenzy |

Erotized Mystic State | Mystic Illumination | |

| Developmental Level | Preoedipal, "paranoid position" | Oedipal, "depressive position" | Postoedipal, Creative |

| Self | Grandiose, narcissistic | Triumphant Guilty | "True" self, identified

with transcendent values |

| Object Relations | Idealized or devalued | Ambivalence God and Devil |

Object constancy Concern for all others |

| Affect | Manic omnipotence Persecutory anxieties |

Ecstasy Erotization Guilt |

Serenity Joy |

| Defenses | Splitting Projective identification |

Repression Reaction formation |

Sublimation |

| Group | Fanatic religious cult | Charismatic | Religious commitment Care of others Moral code |

Table 10.2

Altered States of Consciousness

| Category | Neoplatonic Trance (Mystic Consciousness) |

Dionysian Frenzy |

| Ego functions | Regression and reintegration (regression

in service of ego) Integrative, unifying Basic ego functions intact, even enhanced Higher-level ego defenses only |

Clearly regressed Divisive, disorganizing Repressed ego state gains ascendancy Primitive defenses: splitting, omnipotence and devaluation, denial, projective identification |

| After effects | Associated with "rebirth"

and new personality structure |

Return to same personality structure |

| Object relations | Bad objects integrated Synthesis of internal and external object representation (wholeness) Integration of good and bad ojects |

Bad objects projected Primitive, part objects predominate, often fantasically distorted Dichotomy between good and bad, self and object representations.We and They sharply differentiated |

| Self system | Cohesive sense of self Identity integration Humility, ssense of "we-ness" I-Thou |

Primitive identificatin or fusion

with grandiose self-object Identity diffusion or submission to group identity Omnipotent, narcissistic, magical, manic sense of power I-It |

| Instinctual Vicissitudes | No special object of drives Aggression and sexual instincts sublimated |

Fusion of sex and aggression Aggression and sexual instincts released |

| Perception | Open Clarity increased Heuristic vision Deautomatization Hallucinations rare |

Constricted Intense but confused Ecstatic vision Less deautomatization Hallucinations possible |

| Cognition | Universal symbolism Clear Intuitive, penetrating insights |

Esoteric symbolism Confused Magical insight |

| Affective component | Calm Bliss Peace "which passeth all understanding" Neutrality, paradoxical detachment and commitment, desirelessness Compassion Nonerotic, noetic, heuristic passion Agape Stable, unified Nonambivalent No anxiety |

Excitement Ecstatic frenzy Intense excitement, restlessness "Manic" quality, hysteroid, frenetic No compassion Erotic Eros Unstable, spreading, contagious Ambivalent Great anxiety, if not ritualized |

| Social implications | Sense of being like others Humanizing Maximal integration of both individualness and groupness Intellectual functions still intact Rarely drug induced No ritualization Crosses cultural and historical lines Complex Inclusive No scapegoating Cotensive (Burrow) |

Sense of specialness and superiority Dehumanizing Mob, cult, group instrument of collective forces Intellectual functions suspended Often drug induced Ritualization Bears stamp of particular culture or subculture Simplistic Exclusive Scapegoating Ditensive (Burrow) |

| Group implication | Task-work group (bion) Union based on shared vision and task |

Basic assumption group phenomenon Union based on dogma |

| Value orientation | Ethical Individual and social responsibility Humility Creative Humanizing Truth Sense of sacred |

Moralistic Group responsibility only Omnipotence Noncreative Dehumanizing Idolatry Sense of magical |

Methodological Considerations

The problem with the scientific study of mystic states is primarily methodological. We must first raise the question of whether subjective experience, especially the ineffable, non-objectifiable subjective states that characterize mystic and religious experience, can be scientifically studied at all.

Let us examine first the question of whether empathy might be used as a scientific tool for studying subjective experience generally. Then we will consider the more specific problems associated with mystic states. The phenomena of empathy suggest that individuals are far more contiguous than our usual "objective" perception would indicate. In his original description of empathy, Waelder (1960) described the scientific merit of empathy as an approach to human subjectivity. More recently, Basch (1983) described empathy "as the highest transformation of affective communication ... a form of cognition, value-free and open to scientific evaluation." Margulies (1984) has also emphasized the legitimacy and importance of subjective experience as scientific data, and of empathy as a scientific instrument.

When it comes to mystic states of consciousness, however, their apparent discontinuity from everyday objective consciousness raises serious problems for the use of the "empathic" method to study states of consciousness for which one has no memory traces. How can we empathize with someone who is devoting a life to the mystic way when we have never been on that road, much less had a mystical experience? There are limitations of empathy and objectification of mystic states, and therefore, of the scientific study of religious experience and mysticism.

Despite their baffling obscurities, Freud believed dreams to be the royal road to the unconscious mind and proceeded to examine them rationally by the exploration of his own dreams and those of his patients, using the method of free association (Freud [19001 1961). Stahl (1975) has suggested that Freud's method of dream analysis may serve as a model for studying mystic experience. In such an approach, the problem of the empathic limitation might be partially overcome by having the scientific student of mysticism personally undergo training in the mystic way and then examine personal experiences as rationally as possible, comparing them to those of colleagues undergoing the same experiential learning experience. Notable autobiographical accounts of such a disciplined self- examination of a personal transformational experience have been reported by the psychiatrist Hans Syz (1981) and more recently by the Indian psychiatrist Ravi Kapur (1985).

A Psychological Theory of Mystic States: Trigant Burrow’s Cotention

Although avowedly non-mystical, the "phyloanalytic" approach to human behavior developed by the former psychoanalyst Trigant Burrow and his associates (1964, 1984) contains striking similarities to some of the more recent developments in meditation research and the consciousness disciplines that have attempted an integration of Eastern practices, such as Yoga and Zen, into the frame of empirical psychological study and research (Walsh 1980; Gellhorn and Kelly 1972; Tart 1975; Shapiro and Walsh 1985; Green and Green 1977).

In his concept of the "organism as a whole," Burrow denotes a total action pattern ("cotention") that is a primary physiological given. Burrow views the so-called normal world of symbols and objects as an aspect of secondary distortion and social conditioning through language and family life. This prevailing social conditioning results, he believes, in a partitive, egocentric behavior pattern ("ditension") responsible for much of our interpersonal and social strife. According to Burrow, man's "egogenic" strivings represent a deviation, a "decentering" from the primary mode of human phylic solidarity with fellow humans. Burrow utilized group techniques to diagnose and correct the excessive emphasis of each member's "I-persona" (similar to narcissism) as expressed in the "ditentive mode."

His description of "cotention"–a time-limited state of organic continuity with others and the world associated with a decrease in egocentric striving-is similar to a mystic state. Burrow spent many hours engaged in solitary self-reflection in order to try to understand tensions and reaction patterns, as he called them, which seemed to be experienced in the cephalic region of the head during the usual ditentive state. It was during this process of self-reflection that he became aware of a different subjective reaction of wholeness and calm which he termed "cotention" to distinguish it from the more partitive, striving, ego-related ditensive attitude so prevalent in the behavior of himself and the other colleagues in his research group.

Burrow's view that the cotentive reaction pattern had a biological basis in the brain provided a link to the physical, comparable to Yoga. Another "mystic" feature of Burrow's thought is his insistence that there is another deeper, more basic approach to reality that does not involve the symbol. Thus, Burrow's cotention, like mysticism, becomes another, more direct way of knowing. The experience of cotention involved distinct physiological features (e.g., steadying of eye movements, decreased respiration) as well as mental features (sense of calm and social affinity). These were so qualitatively distinct from the usual ditentive mode of "normality" that Burrow felt a fundamental, organic aspect of the species must be involved, one which had a neurophysiological basis (Burrow 1984). In contrast to the symbolic, partitive ditentive knowing associated with symbol and language, Burrow speculated that cotention must represent a fundamental holistic mode of the species or, as he preferred to say, of the phylum. Hans Syz has suggested that Burrow's choice of the broader term phylum may reflect an unconscious preference for a more cosmic term than Species (Syz 1981).

Essentially, Burrow came to believe that psychoanalysis, ill treating individual neuroses, was dealing with secondary symptoms of a more basic, organismic dissociation or displacement-the "social neurosis" endemic to humans. This organic decentering, he proposed, is too entrenched and too fundamental to the functioning of the organism to respond to the "mental or symbolic plan of enquiry" of traditional psychoanalysis or psychotherapy. He wrote that these ditentive deviations are universal and, like the proverbial mote, present in treater as well as patient, in investigator as well as research subject. Therefore, the usual techniques of psychoanalysis or psychotherapy cannot resolve them, for they cannot be objectified 'in the patient. The cure, he proposed, requires a group format in which the therapist and group member are equally subject to confrontation and interpretation. This method of social analysis he called phyloanalysis.

In terms of specific techniques developed from his researches to produce the desired cotention, he encouraged the subject to sit or lie down in an attitude of repose and to become increasingly sensitive and aware of the position of the eyes when in their "relaxed" state, i.e., when not engaged in "symbolic or projective attention." With the eyelids closed, the eyes are focused as steadily as possible on a point a few yards away directly in front at the center of the field of vision. An effort is made to exclude the usual flow of thoughts and distractions. These techniques were arrived at utilizing physiological correlates (e.g., slowing and deepening respiration) to promote and enhance the generally latent "cotentive" mode.

Burrow noted that these efforts to center on a more harmonious integration included the respiratory, vasomotor and circulatory, and cerebral activity. His descriptions are similar to the claims of the mystics that their discipline affects the basic physical and metabolic functions of breath, circulation, digestion, and hormonal activity as well as the mind. Parenthetically, it was from similar observations of yogis that the idea of biofeedback developed (Green and Green 1977).

In summary, Burrow proposed that the problems of human beings are basically socioneurotic problems; i.e., individual neurotic difficulties are derivate of a primary specieswide defect in sociality. Burrow hypothesized that this social defect is due to our unique symbolizing and language facility, which has deflected the innate biological sociality of humans into an excessively self-referent attitude or mode. Burrow claimed to be able to detect and clarify this self-referent, acquisitive, competitive mode by examination of human interaction in small groups. He called this mode of behavior "detention." He related the ditentive mode to what he called the "I-persona"-the competitive, self-centered motivations of humanity as a whole.

After years of research and, we would add, mounting frustration and discouragement regarding the resistance to change associated with the ditentive attitude in his experimental groups, Burrow reported he was able to detect evidence of a more fundamental, latent cooperative mode in himself and others. He termed this cooperative mode "cotention" and published studies in which he reported differences between cotention and detention with electroenccphalographic and other neurophysiological measurements. He proposed that the cotensive mode was derived from the primary identification between infant and mother. He sometimes called cotention the "preconscious mode. Although some scientists and therapists (for example, the family therapist, Nathan Ackerman) were attracted to these ideas, Burrow's main advocates at the time were creative writers and artists (D. H. Lawrence, among others) (Burrow 1964).

Burrow went against prevailing individualistic trends in Western thought and was repudiated by most of his fellow psychoanalysts. He emphatically disavowed mystic, teleological, or religious elements and persistently sought physiological correlations and scientific support for his findings. Nevertheless, his view of an innate communal solidarity of the phylum, as well as the somewhat contemplative techniques he used to discover the cotensive mode, has mystical, if not religious overtones. Furthermore, the dualistic nature of his theory, with the struggle to overcome detention (bad) and enhance cotention (good) may reflect his own repudiated Christian background (his mother was a Southern grand dame and a Roman Catholic) (Syz 1981).

A Case Example: Sri Ramakrishna

The life and experiences of the Indian saint Sri Ramakrishna afford us an opportunity to understand the nature of mystic experiences. Set in a religious context, Sri Ramakrishna's experiences were varied and spontaneous, as well as induced, and they had a profound impact on his life as well as that of his culture. The knowledge about his early childhood and even later adulthood come to us from hagiographic accounts of his disciples (e.g., Saradananda [1911-16] 1978), where fact and legend have merged. This very fact reveals not only the Indian attitude toward history but also a tradition in which myth making about heroes has been second nature. A religious man and especially a mystic lends himself to the forces of culture, thus legitimizing his role as a pathfinder.

Ramakrishna was born in 1836 in a village near Calcutta in the province of Bengal. Biographers tell us, from anecdotes and memories of contemporaries, that his parents themselves had visions relating to Ramakrishna’s birth. As a child, he was known to be unruly, mischievous, and given to impersonating women. In one incident he was reported to have entered a strictly regulated women's quarter dressed as a woman and gone unrecognized. He especially enjoyed devotional singing and was reported to be lost in the rapture of the rhythm. His father's sister was known to have been possessed by the spirit of a goddess, and Ramakrishna later recalled that it would have been splendid if the spirit had possessed him. At least on one occasion, the story goes, while participating in worship, Ramakrishna became so engrossed that he lost consciousness. Later accounts of such behaviors characterized them as trance states, but his father was worried that the young boy suffered from "fits and his mother was concerned that he had come under the influence of an "evil eye."

After his father’s death from chronic dyspepsia and dysentery when the boy was about seven, Ramakrishna became restless and pensive and was known to wander alone at the cremation grounds. He frequented the pilgrim-house where the wandering monks lodged to become familiar with them, but the mother feared that he might be tempted by the monks to go away with them. In the following months, Ramakrishna remained preoccupied and had episodes of loss of consciousness and of his sense of self and time. Some years later he came under the protection of his eldest brother, who had migrated to Calcutta to make a living as a teacher and priest and who was also known to have premonitions about the future. It is said that he predicted the event of his wife's death accurately. Ramakrishna became a temple priest at the age of nineteen. Soon after that his brother died.

Following his brother's death, Ramakrishna's behavior became strange, his mind agitated. He spent hours in worship of Kali, the mother goddess of Bengal, and in meditations. He felt despairing and desperate and contemplated suicide. He later described his state of mind:

Instantly, he had a vision that he described as follows:

It was as if the houses, doors, temple, and all other things vanished altogether, as if there was nothing everywhere! And what I saw was a boundless infinite Conscious Sea of light! ... a Continuous Succession of Effulgent Waves coming forward, raging and storming ... and lost all sense of consciousness." (Saradananda [1911-16] 1978, 163)

His behaviors, especially his tendency to fall into a state of unresponsiveness and sometimes unconsciousness, led those around him to suspect insanity. Doctors were consulted and various medications given (Saradananda [1911-16] 1978, 164, 165, 175). His mother thought that lie was possessed by a ghost and brought him to an exorcist (Saradananda [1911-16] 1978, 202).

During the years that followed, Ramakrishna came in contact with a series of individuals: sponsors, intellectual and religious leaders of the community and, most important, both mentors and disciples. Having received the patronage of a wealthy sponsor, he returned to the Kali temple in Calcutta and met with the curious, the devout, and the skeptic alike. It was here that his first mystic experience Occurred, but there was no end to his travails. He continued to be rapt in worship and meditation, caring not for his physical well-being, and was known to frequently pass into altered states of consciousness. His family’s concern for the health of his mind was unabated, and they arranged his marriage, hoping that would alleviate whatever was ailing him. However, Ramakrishna was not to be deterred from his path of seeking divine vision.

A holy woman entered into Ramakrishna’s life, taught him specific devotional practices, and arranged for a conference of scholars and pundits to pass judgment on his religious authenticity A model existed, particularly in the history of Bengal, of a saint whose emotional frenzy and ecstasy was a matter of folklore. The assembled group conferred a similar status on Ramakrishna. In a sense, at this point, he was invested by the community with holiness.

The next twelve years Ramakrishna spent in intense religious practices from every known tradition, including Islam and Christianity. The intellectuals who spearheaded reform movements within Hinduism, incorporating Western influences, came to regard Ramakrishna as a major contributor to the resurrection of Hindu ideals. Finally, in the disciples-especially Swami Vivekananda, whose arrival had been accompanied by another divine vision, Ramakrishna's spiritual leadership in India was consolidated. The bonds that developed between him and his disciples, life particularly Swami Vivekananda, brought organization and stability to the life of Sri Ramakrishna, elevating his message to the status of a movement in India.

The hallmarks of Ramakrishna's mystic experiences are in concordance with our understanding of such experiences. Spontaneous or induced, the experiences had in common a profound affective tone. There was a perception of interconnectedness of all things, so that the boundaries between subject and object were obliterated and the predominant cognitive aspect was of a religious nature.

It must also be emphasized that the period prior to his ascension to sainthood was one of intense psychological turmoil, often mistaken by those around him as possession or insanity. (June McDaniel [1987] has extensively treated the subject of madness and ecstatic states in relation to culture and religion.) But when the community reinterpreted his experiences and set Ramakrishna into the prevailing religious tradition, his experience was legitimized. Also, the succession of mentors and disciples was an important grounding. In his incorporation of deities of other religions, Ramakrishna restored to his followers a sense of mastery over the Western missionaries and a pride in their native traditions during a time of onrushing Western modernity in India.

Mysticism and Creativity

Many scientists emphasize the role of a mystical perspective in their own scientific breakthroughs. Much of Newton's theoretical system developed from a mystical experience (Bion,1977). Such developments occur in agnostic as well as religious persons. The mystic vision appears to be a central stimulus for religion, but once religion becomes institutionalized, mysticism may have little to do with religious practice and may be held ill suspicion by the religious hierarchy. It seems important, therefore, to examine mystic states in their own right, independent of any theological or teleological assumptions. For example, poets and writers have described the instantaneous nature of inspiration in which the entire conception or idea or story is grasped, which may then require months of working out through rational, empirical means (Ghiselin 1963).

Nathaniel Ross states that regressive unions that infiltrate the more objective, reality oriented ego perspectives may even be required for optimal function (1975). Rose describes how in creative inspiration, the boundaries of our separateness and identify "are repeatedly dissolved and recreated as we dip back and re-emerge from looser and earlier arrangements of reality." He has described case material of pathological, normal, and creative fusion (1972). A different view is expressed by Singer (1977) who views this open, flexible outlook as part of an adult personality style rather than a regression.

Greenacre wrote that some gifted children describe ecstatic states of a "peculiarly exalted type." They combine a prominent mystical and religious flavor with collective and cosmic themes. Such gifted children describe a haunting and compelling sense of boundlessness and a general sense of power and awareness that reach beyond the limits of the self In some ways, such experiences of gifted children may represent precocious experiences of unitary consciousness. Although Greenacre described this material within the context of classical psychoanalytic theory, she nevertheless noted that creative ability that appears in this form may be "beyond the scope of psychoanalytic research" (1958).

It has been proposed that religious practices and their mystic coloring may derive affective overtones from their association with important early relationships, essentially serving as "transitional" objects or phenomena (Winnicott 1953). Greeley (1975), following Eliade (1964), sees mystic experience as a return to a powerful primordial myth of paradise, common not only to primitives but to all humans. Some of the profound affective experience associated with mysticism reflects a vision of reality distinct from "objective" experience, which yet has a particular clarity and meaning of its own. We would consider the transitional experiences described by Pruyser (1984) in regard to imagination and childhood and Csikszentmihalyi's (1975) concept of play and "flow" to be developmental forerunners of mature mystic and creative experiences. (See, for example, DeNicolas's Powers of Imagining [1962], a study of Saint Ignatius of Loyola.) The capacity for creative imagery is also highly correlated with hypnotizability (Hilgard 1986).

The Eureka Experience

The so-called eureka experience generally associated with a creative breakthrough may be considered a secular variant of mystic illumination. The word eureka derives from the Greek, meaning simply, "I've found it." The paradigm for the eureka experience was Archimedes who, after long study and concentration, suddenly discovered in a flash how to determine the alloy in the king's crown. What we wish to emphasize by this term is the human capacity to become rapt-to develop a total psychological absorption in the object. This process involves a period of disciplined concentration and screening out of distractions, followed by a sudden breakthrough of insight in which some hitherto unknown experience or previously unorganized concept suddenly becomes manifest. The eureka experience has an emotional component of exhilaration, even ecstasy, and is a variant of mystic experience.

Without the capacity for becoming rapt (carried away) by the particular subject, conflict, or problem, there can be no subsequent eureka experience. The relationship of such processes to the unconscious, and the breakthrough of previously repressed or unintegrated contents of the mind into consciousness, as well as the ego capacity to "let go" without becoming disorganized (Rose 1972), have been described in the psychoanalytic literature as a psychological means of switching from a more motivation-powered and problem solving behavior to a process in which one becomes so totally absorbed in the object of study that one "loses oneself," enabling the individual to "see" new relationships and connections not previously recognized.

The "high" associated with the eureka experience is complex. Like mystic experience generally, it probably includes a neurophysiological discharge mechanism, which is given a particular character by aspects of the object-relations history of the individual.

The eureka experience, like mystic states, is frequently associated with the presence of another persons guide, a mentor. If such a guide or mentor is not present, there is usually a highly cathected object representation, such as God. The unusual work and discipline involved in the preparatory stage of such experiences should be emphasized, as well as the subsequent working through of the insight.

The eureka experience often involves resolution of internal conflict, particularly around narcissistic phenomena. In such cases a change and alteration in the self follows the experience (Kohut 1971, 1977). After the eureka experience, there is a new knowledge and there may be new sense of self as well. Despite the unique subjectivity of the eureka experience, its most significant and meaningful forms invariably involve a highly developed social context. Finally, the eureka experience is almost always experienced as healing, as therapeutic. In this respect it is similar to descriptions of the "aha" experience associated with insight in psychotherapy.

Mysticism: A Darker Side?

Expressions of the mystic and of the fanatic or cult member seen at times dangerously similar. Both are fearlessly sure of themselves. Fanatic zeal and moral passion or commitment are not easily distinguished. As noted previously, such observations suggest different levels of mysticism or unitary consciousness. In table 10.1, different levels of development are linked to archaic and higher mystic states. It also seems useful to compare various affective-cognitive expressions of unitary consciousness with an assessment of the object relations in any given case. Existing theory has no place for higher forms of unitary consciousness, such as true mystic states or, for that matter, creative illumination. The differentiation of such "higher" states from pathological states is as yet not well understood, and the distinctions in the tables 10.1 and 10.2 must be considered tentative. In addition to the developmental model in table 10.2, a phenomenological examination of "higher" and "lower" mystic states is found in table 10.2.

Even the most esteemed mystics may at times explain the world's problems with simple formulas and do so with sublime freedom from self-doubt: all evil apparently lies outside the explanatory system. One cannot help but wonder whether this treatment of die darker side constitutes a form of "pathological mysticism" that distorts rather than augments reality. It would seem that it does and that the mystic vision is "subject to many diseases" (Buber 1970). The presence of projection and a hated scapegoat signifies the presence of such diseases (Cohn 1970).

Cult members and fanatics generally seem to regress to and remain fixed at the level of archaic merger states, whether ecstatic or traumatic. Such states are characterized by loss of and withdrawal from the object and a deadening of human sensibilities. The element of human cooperativity is missing. There is destruction of the necessary kinship with others which alone can authenticate and complete the self. What then happens to the solitary mountaintop mystics in the best of the Indian tradition? Even here one finds an intense, devoted relationship to a guru, and if not an actual person, then the memory of such a person, or the image of a God made real and personally meaningful.

In the case of severe narcissistic injuries, on the other hand, the primary other failed the developing self, so that the self may turn for fulfillment, not to the ideal other or the image of that ideal, but to a compensatory grandiose self-image fused with an idealized object. In this case there is no true recognition of an "other," except in the service of the grandiose self. Such individuals may gravitate to religious cults and pathological "mystic" expressions. In such cult members or leaders, other people have no meaning other than as ail extension of the narcissistic needs of the self (or group). Consequently, persons or groups outside the cult easily become targets of hate or violence-even persons previously loved. there is an "addictive" clinging to the cult and its beliefs, which embody the grandiose ideal-self-object merger. In "healthy" or higher forms of mysticism, the capacity for distinction (for "one pointedness") and for clarity of perception parallels the development of unity. It is a paradoxical state.

In pathological forms of cultic belief, there is a similarity to the picture seen clinically in compulsive addictions. There is intense craving in proportion to the absence of any meaningful relationship and commitment. This "emptiness" of the addicted or "cultic" personality presents a severe obstacle to treatment. Whereas writings and poetry of the great mystics, even the most solitary ones, overflow with devotion, there is neither true devotion or commitment in die fanatic cult member.

In some ways the fanatic expresses in such group behavior a caricature of the universal psychosis of social humanity. According to the mystic commentators, this is a disease that all people share: disavowal of the organismic unity with our fellow human beings.

Discussion

Our greatest blessings come to us by way of madness.

Plato, Phaedrus 244A

The phenomena of mystic and creative illumination suggest that there exist quite different states of awareness, dissociated from our ordinary consciousness, which appear suddenly, as if a threshold of some kind had been reached, bringing with them for a limited period of time an altogether different cognitive and perceptual state. From a clinical standpoint we are familiar with pathological or traumatic experiences, memories, and affects, which may be repressed or split off from our usual conscious awareness-possibly to appear later directly or in the disguised symbolic form of symptoms. Thus, the mechanism of dissociation is familiar to us as a primitive defense mechanism and a form of psychopathology. Indeed, we have every reason to believe that there exist quite commonly such pathological forms of religious and mystic experience. The religious traditions in both the West and the East have warned us of "false prophets" and of the narcissistic pathologies to which the spiritual life in its mystic form is susceptible (Merton, 1967).

Saint Ignatius himself was remarkably candid about the "vainglory" and suicidal depression that followed his earlier state of rapture prior to his final conversion at Cardoner, which resulted in a major personality change and the eventual founding of the Jesuit order. What is the difference between these two states in Ignatius? Phenomenologically, they seem much the same if one examines only the experience of the ecstasy itself (Woollcott 1969). The preliminary and subsequent phases are, however, very different. There are many records of experiences of religious and creative illumination in the lives of our greatest poets and saints, including hallucinations, trances, delusions, and loss of boundaries of the self. In fact the very creative power of the vision may be related in the mind of creative individuals with its foreignness, its otherworldliness, its intrusive disruption of their normal consciousness (Laski 1961).

Hallucinations and delusions arc common in the dissociative syndrome of multiple personality, leading frequently to a misdiagnosis of schizophrenia. The dissociative experience itself, especially at the time of the "breakthrough" of dissociated material, seems to be associated with the temporary appearance of disturbances in thought and consciousness, which in clinical experience is generally related to psychosis but in the case of dissociation may express a more temporary disorder. The situation is similar to the psychedelic experience. If the set and setting are supportive, a nonpsychotic, even "transcendent" and ecstatic, transformation of perception and cognition may occur. If the situation is non-supportive, severe anxiety or even psychosis may result.

If we lay aside our clinical bias that mystic states are a form of regressive psychopathology, we confront an interesting observation, which may be expressed in the form of a question. Why would the expression of human creativity and religious genius be connected with a dissociation of experience? Why are mystic states dissociated? Is there something about the content of experiences of mystic illumination that could explain why they so rarely enter our conscious experience, and then only for a short while?

Mystic experiences, including religious and creative illumination, are related psychologically to other dissociative phenomena, such as shamanistic trance, faith healing, hypnotic phenomena, and, on a pathological level, multiple personality. The breakthrough of previously dissociated aspects of experience into consciousness, resulting in a broader, more integrated field of perception, seems to represent a common psychological mechanism that may be associated with integration, healing, and increased well-being, but which may also result in pathological outcomes. The presence or absence of a supportive environment is all important factor ill outcome. This suggests a deep psychological link between mystic states and a deeper level of as yet poorly understood social forces in the personality. Bion has proposed the existence of a "proto-mental state" preceding self-object separation and language acquisition, which may be the source of "basic assumption" group behavior (Bion 1977). This protopathologsocial mental state may also contain deeply repressed or dissociated archaic social tendencies.

Burrow suggested that the "objective" mode associated with self-object differentiation may be essentially incompatible with the initial infant-mother "dual unity," which must be repressed. Mystic and creative illumination may represent more evolved developments of this largely repressed unitary consciousness. I say "more evolved" because we do not know what the infant experiences. The infant's brain and neurophysiology is fit different from that of the adult. Although mystic states have been described in children and arc fairly common in adolescence, they reach their full state only in adulthood.

Since the mystic vision of identification with all other beings seems much the same in different cultures and periods of history, this experience may spring from our innate neurophysiology. It is as if the mystic illumination represented a social ethic embedded in our brain and mind, apparently contradicting our biological strivings for instinctual gratification.

Our thesis is that mystic states represent a breakthrough that links the developmental line of largely dissociated experiences of unitary consciousness with the developmental line of the self and object relations which we experience in our ordinary "objective" consciousness. Mystic states as well as other related states (religious awe, eureka experiences, numinous experiences) disrupt the homeostasis of the self and its "objects.' creating a risk of regressive and especially narcissistic solutions, but also the possibility of a more advanced level of development of the self and its relationships. Creative forms of mystic enlightenment involve a more integrated view of the world and a broader sense of relationships, including social ethics and values.

Paradoxical Integration

There appears to be an inherent conflict between the yearning for fusion associated with the largely dissociated experience of unitary consciousness and the strivings for individuality. Mystics at their best seem to achieve an integration between polar opposites. The advanced yogi may seek samadhi or "oneness with God." This union is associated paradoxically with a separation of and control over the demands of the instinctual drives of sexuality and aggression, as well as functions of the body not ordinarily under the control of the will (e.g., respiration, eye movement). In other terms, the yogi's achievement of the unity of samadhi is associated paradoxically with a high degree of "field independence" through control of the breath and concentration.

Thus, on close scrutiny, the achievement of mystic states seems to be associated with certain paradoxical developments of an equally high degree of perceptual clarity, "one-pointed" attention and concentration, motor control, affective modulation, ethical discrimination, and independence in relationship to the environment, which are generally associated with a high level of ego strength and maturity of object relations. Thus, efforts to explain mystic states as regression to infantile states do not correspond to clinical observation.

Summary

We may summarize our hypothesis of a developmental line of unitary consciousness as follows. We begin life in a state of union with the environment. Consciousness itself springs from this unity or is this unity. Without the response of the consciousness of another, neither consciousness nor life could proceed further. Thus, in its fundamental nature, consciousness is interactive. ("The very Being of man ... is the deepest communion" [Bakhtin 1961].) We have no direct knowledge of what the infant actually experiences of this primary identification or consciousness. What we have done is to adultomorphize about it on the basis of what we observe in children, in the mystic, or in regressed patients. There seems to be a consensus among developmental psychologists, however, of the role of a firm establishment of this "primary unity" between infant and mother for subsequent development (Little 1981; Mahler, Pine, et al. 1975). Even from its earliest origins, this primary bond is characterized by a synchronous rhythmical connectedness between two quite different organisms. "Those fortunate Individuals who, in early infancy, have been able to enjoy and internalize the emotional experiences of a rhythmical adaptive interaction of the mouth differentiated from the breast are receptive to later experiences such as human sexual love and aesthetic and religious experiences" (Tustin 1981).

Cognitive and perceptual development create awareness of disunity-of separation between the self and the environment-and the basic unitary experience of interconnectedness of the child is lost. Throughout the seperation-individuation phase (Mahler, Pine, et al. 1975) and, indeed through life, the individual struggles to differentiate his or her unique humanity from the surrounding human and nonhuman environment (Searles 1960).

In our unconscious, however, remain traces of our original sense of oceanic continuity and connectedness with the universe, which in our development we have dissociated and put behind us. We are ambivalent toward this primary state of unity; we fear becoming immersed again in its limitless chaos yet long to recapture its blissful interconnectedness. We have referred in previous studies to this basic human ambivalence as the "fusion-individuation conflict" (Woollcott 1981). The fusion individuation conflict is only resolved by means of a continuation throughout life of various direct or symbolic forms of merger experiences between the developing self and the dissociated experience of unitary consciousness and its derivatives.

In this conception, the unitary model of consciousness evolves in a parallel developmental series with, and in proportion to, the developing strictures of the self and object relations, and of the brain itself Connections between the developing self and object relationships, the evolving line of development of unitary consciousness, and the neurophysiological structures of the brain are manifested by complex affective-cognitive states such as awe, wonder, the numinous, states of creative insight, eureka experiences, and mystic states. The fact that such experiences occur only temporarily in brief "quanta,' as well as their cognitive and space-time distinctions, reflects the discontinuity or dissociation which exists between the development of the self of everyday reality and the development of unitary consciousness. Finally, the meaning of the unitary states and their "cognitive" component of a deep fraternal bond among people which occurs during mystic experience is unknown.

In conclusion, there are two paradoxically related experiences that are the focus of our study of mysticism. One is the solitary individual's experience of a sense of interconnectedness of all things. The other is the primacy of relationality in human experience. The true mystic unity is a primal dynamic connection, a uniting. A so-called mystic experience that leads away from relationships with others and the world, or one that divides relationships between the all good and the all bad, between the holy and the evil, is a false or pathological mysticism. True mysticism is characterized by an identification with all beings. This is the radical mystic experience of the poet John Donne, expressed in "No man is an island": How do people who have never had a mystic experience appreciate the poet's creation? People may not understand the poet's mystic experience per se, but they can "empathize" with the poet’s insight or vision. The poetic vision stirs something deep inside all of us, an essential affinity with others and the world.

This paradoxical connection between mystic illumination and relationality and love is eloquently expressed by the blind poet Jacques Lusseyren, who lost his eyesight through an accident at the age of seven and a half. He later wrote (in "The Blind in Society"):

Barely ten days after the accident that blinded me, I made the basic discovery … I could not see the light of the world anymore. Yet the light was still there… I found it in myself, and what a miracle! –It was intact. This "in myself," however, where was that? In my head, in my heart, in my imagination? ... I felt how it wanted to spread out over the world. ... The source of light is not in the outer world. We believed that it is only because of a common delusion. The light dwells where life also dwells: within ourselves.... The second great discovery came almost immediately afterwards. There was only one-way to see the inner light, and that was to love. (Erikson 1981, 330)

Notes

1. Julian Jaynes (1976) describes consciousness as follows: "We have said that consciousness is an operation rather than a thing, a repository, or a function. It operates by way of analogy, by way of constructing an analogue space with an analogue 'I' that can observe that space and move metaphorically in it. It operates on any reactivity, excerpts relevant aspects, narratives and conciliates them together in a metaphorical space where such meanings can be manipulated like things in space. Conscious mind is a spatial analogue of the world and mental acts are analogues of bodily acts. Consciousness operates only on objectively observable things" (65-66).

2. Ludwig (1966) defined altered states of consciousness as any mental state induced by various physiological, psychological or pharmacological maneuvers or agents which can be recognized subjectively by the individual himself (or herself) or by an objective observer of the individual as representing a sufficient deviation in subjective experience or psychological functioning from certain general norms for that individual during alert, waking consciousness. This sufficient deviation may be represented by a greater preoccupation than usual with internal sensations or mental processes, changes in the formal characteristics of thought, and impairment of reality testing to various degrees.

References

Bach, S. 1977. "On the Narcissistic State of Consciousness." International Journal of Psychoanalysis 58:209-322.

Bakhtin, M. M. 1961. Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Basch, M. F. 1983. "Affect and the Analyst." Psychoanalysis Inquiry 3:691-703.

Bion, W 1977. "The Mystic and the Group." In Seven Servants, 62-71. New York: Jason Aronson.

Buber, M. 1970. I am Thou, trans. Walter Kaufinan. New York: Scribner’s.

Burrow, T. 1937. "The Organism as a Whole and Its Phyloanaiytic Implications." Australian Journal of psychological Philosophy (December).

–. 1964. Preconscious Foundations of human Experience, ed. W E. Galt. New York: Basic Books.

–. 1984. Toward Social Sanity and Human Survival, Selections from His Writings, ed. A. S. Galt. New York: Horizon Press.

Colin, N. 1970. The Pursuit of the Millennium, revised edition. New York: International Universities Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. 1975. Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: The Experiences of play in Work and Games. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

d'Aquili, G. E. 1986. "Myth, Ritual and the Archetypal Hypothesis." Zygon 21 2(June): 141-60.

Davidson, J. 1976. " Psychology of Meditative and Mystic States of Consciousness." Perspect. Biol. Med. (Spring): 235, 345.

Deikman, A. J. 1963. "Experimental Meditation." Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 136:329-43.

–. 1966. "Deautomatization and the Mystical Experience." Psychiatry 29:324-38.

DeNicolas, A. T. 1962. Power of Imagining, Ignatius of Loyola: A Philosophical Hermaneutic of Imaging Through the Collected Works of Ignatius de Loyola, translation. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Eliade, M. 1953. The Yearning for Paradise in Primitive Tradition: Diogenes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

–. 1964. Shamanism: Archaic Technics of Fantasy. New York: Pantheon.

–.1975. Patanjali and Yoga. New York: Schocken.

Erikson, E. H. 1981. "The Galilean Sayings and the Sense of ‘I.’" Yale Review 70:321-62